Layering time: experiments with medium format photography

Rose:

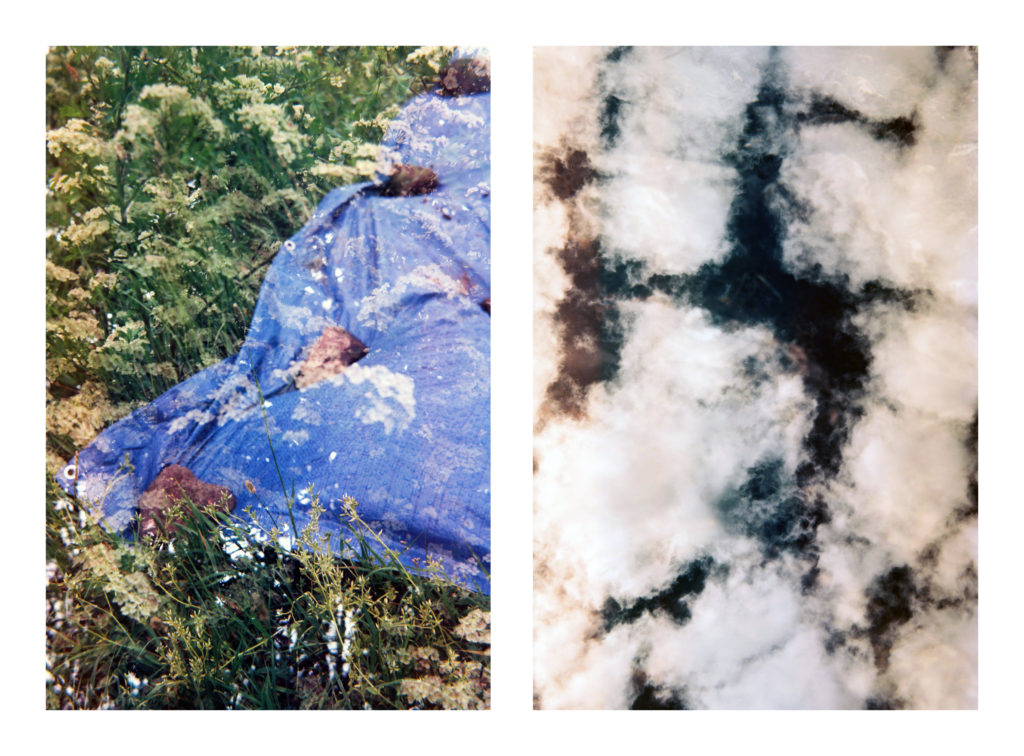

An ordinary blue tarpaulin billows cloud like, anchored by stones. Strewn through and across it, an eruption of hawthorn flowers. It is a scene of early summer; delicately layered into abstraction. This is one of Rob’s double exposure medium format photographs. He took the first ones on a visit out to site, calmly aiming the camera amongst the clutter and bustle of the excavation. This mode of exposing one scene onto another holds particular fascination to me. In layered light two moments in time, two scenes, are merged. Bits and pieces of one flex and unfold with the other, entangled in a moment.

The quality of Rob’s photos using this technique chime with ideas of time in archaeology. Many years ago I saw a talk by Mark Knight called ‘Speed’ [2005, Theoretical Archaeology Group (TAG), University of Sheffield]. In it, I remember an old photograph of a London street, taken using a long exposure. In the seconds that ticked by as the photo was taken, elements of the scene vanished, or were blurred into obscurity, “…until our duration of exposure renders people into ghosts and instead switches the emphasises on to the material, the lived within” (Knight 2005). Mark, in his wonderfully imaginative way, wove between this image and the archaeological record, using photography to think about ideas of archaeological duration and depths of field.

Photography offers a particular ‘way of seeing’ that somehow makes it easier to grapple with the abstract notions of time and change with which we are faced in archaeology. It is also a thoughtful practice. Watching Rob carefully select, frame and layer particular elements brought home how carefully we choose at what ‘moment’ we record the trench, what angle and features we draw out. These become the only record of layers that cease to exist, that disintegrate and scatter. Photographs and drawings become the selected earthy memories of that site. Rob’s double exposures encourage the question of what happens when we put layers back together? How does the merging of two images change our view of them individually, yet also create a new narrative, a new feel for place and time? What ‘exposures’ in the archaeological record result in one layer being more visible than another, or in a stratigraphy forming new impressions of the past?

Returning to the images themselves, what draws me to them most is their quiet, loose abstraction. They suggest these ideas of time without being explicit. They seem to visually rove, not quite fixed. The combination of textures often create a strange sense of movement; movement as seen in a memory. And the quality of the images themselves suggests age, whilst small hints within them spark with modernity.

They are also an echo of Rob as photographer: calm, attentive observation and creative care; piecing together fragments to form a new way of seeing the archaeological landscape.

Rob:

Over the years, I’ve put together a ‘toolkit’ of audio and visual tools – sound recorders, microphones, cameras, and so on – that I use on the fieldwork that supports my artwork. All (relatively) neatly packing down into a large camera bag, this toolkit allows me to bring existing ways of working to different sites, and also to explore new site-informed practices using familiar equipment.

One of the heaviest items in the camera bag is an old Zeiss Nettar medium format camera from the 1940s, which used to belong to my Grandad. The camera lens folds out of the body in a concertina motion; still smooth and free of light leaks after all these years. Medium format cameras take 120 film, which has a far larger negative size than 35mm film (the Zeiss works on a 6×9 aspect, with a frame size of roughly 56 × 84mm). This means that 120 film can produce richly-coloured images at a higher resolution and with less grain or blur compared to 35mm film.

Shooting with the Zeiss can be a bit of an improvisation. There is no ‘viewfinder’ to speak of, only a tiny lens which gives a rough idea of what you’re pointing the camera at. Perhaps pointing is the wrong word, given that I generally end up cradling the camera at waist height: shutter speed and aperture set; peering down at the millimetres-wide inverse image of the landscape (often obscured by the glare of the sun), and then with slight trepidation, pressing ‘click’ on the shutter lever.

Regardless of how remote the locations I’m working in, and how light my equipment pack needs to be, the Zeiss usually finds its way along. There is something very pleasing about the slowness of actions it encourages; each setting manually adjusted, a stillness in your body as you make micro-changes to the camera’s orientation. This process is similar, in many ways, to the binaural soundwalks I take: stopping for quiet moments; becoming attuned to the small shifts in a landscape.

Soundmarks is primarily a project centred around Rose’s visual art and my sound art. So why am I taking so many photographs? Partly, out of habit: practiced ways of getting to know a landscape. But, also as a thinking process. Early on, I realised that experimenting with double exposures on the medium format film could somehow echo the layerings of time and material being uncovered around the trench. So I began layering images from the site onto each other; taking a picture and leaving the frame un-wound on, to be exposed again.

This process made me think differently about looking in the landscape: once one image had been taken, I kept an impression of how it might look on film in my mind, and sought out patterns, colours and textures that might somehow resonate with it as I walked through the village and surrounds. Of course, this would all be much more easily done with a digital camera and Photoshop, but there is something interesting – and inherently uncertain – for me about the slow accumulation of analogue film images made in this way. They resonate, too, with the ‘pattern thinking’ of one of my favourite artists, the Hungarian György Kepes, who devoted much of his career to conceptualising how unusual visual shifts in scale and form might hold the potential to generate new understandings of the environments around us.

These images are less about product than process. Working in this way around Aldborough during the dig, I began to think more deeply and clearly about archaeological theories and practices, and how they might be brought into conversation with art: a slow process of layering and accumulation.